What Japanese Companies Can Learn from Mainoumi about Growth Strategy: Management of Agility and Wisdom

Known for her research on Japan, including her recent book “Japan Re-Emerges”, Professor Ulrike Schaede of the University of California San Diego, School of Global Policy and Strategy, spoke at IGPI’s symposium ”The Revival of Japanese Companies: Is Japan Back?” held in late 2024. During the session Professor Schaede, who is also a member of the Advisory Board of IGPI Group, highlighted the unique strengths of Japanese companies that are often overlooked. In today’s conversation, IGPI Group CEO Takashi Muraoka and Professor Schaede delve deeper into the topics of the symposium to explore what Japanese companies can do to grow even stronger.

Differing Perceptions of Resilience between Japan and the U.S.

Takashi Muraoka Professor Schaede, you have been actively sharing your insights on the management of Japanese companies through books, media, and events. What kind of responses have you received?

Ulrike Schaede I have received two types of responses. The first is negative, refusing to accept my message, including even comments such as “she doesn’t know Japan”. The other is positive, but still with an underlying tone of pessimism, namely, an agreement that “not everything is bad in Japan and not everything is great in the U.S”. Yet still, even those in agreement still view their own company and work negatively. It’s this persistent pessimism in Japan that makes me continue my work.

Professor Schaede’s recent book,

“Japan Re-Emerges” (Nikkei Publishing)

Takashi Muraoka Professor Schaede, while you are an optimist you are not simply a Japanophile; you understand Japan’s strengths and challenges based on your findings from comparing data with other countries. I think the key word here is “optimism”. When the U.S. entered economic depression three to four decades ago, Americans did not give up their belief in their economy, did they?

Ulrike Schaede It is these differences in thinking and approach that are interesting to me. The one you mention relates to resilience. Americans are very proud about the “resilience” of their economy. What they mean by that is the speed to recovery after a shock. That’s actually their textbook definition of the word. Therefore, even though the American economy is highly volatile and there is disparity between the rich and the poor, Americans believe in their ability recover quickly. But my sense is that Japan’s definition of “resilience” is quite different. I think it’s close to the concept of heijunka –the steady flow – of Toyota Production System. In that system, the important thing is to limit the amplitude of the shock, and continue in an even flow. Thus, when a shock occurs, the focus is on limiting the damage, not letting it happen and then deal with the recovery.

It is not a question of which is better. These are tradeoffs, and both come with costs and benefits. Speed versus stability, quick change versus incremental adjustments – it depends on what you value.

Japan, in my view, prefers stability. As a result, Japan trades in speed of corporate reorganization for limiting unemployment and social unrest. As I say in my book, 30 years of stagnant GDP is the price Japan has choose to pay for great societal stability. That was very costly. But arguably, we now see that America’s choices over the past 30 years are even more costly.

Takashi Muraoka It is true that the Japanese try to minimize damage, but historically, the fluctuations have not always been limited. For example, Japan has recovered from the severe post-war economic crisis, and during the Meiji Restoration, Japan transformed from a weak nation to one that stood alongside Western powers in the global stage. Japan has also rebuilt itself from devastation, after suffering natural disasters such as earthquakes.

Ulrike Schaede In the cases of the post-war era and Meiji Restoration, Japan was positioned as a follower, and had a lot to learn from the world. However, the current situation is different. Japan is at the forefront of technology, and companies compete at par with the world’s leading nations. This transition from a follower to a competitor at the global technology frontier brought a strategic inflection point for Japan’s industrial architecture.

Three Opportunities from Population Decline

Takashi Muraoka An inflection point could become a risk or opportunity depending on how you view it. For example, Japan was the first in the world to enter population decline, and by the year 2100, the population is estimated to halve from the current level. Considering Japanese society as a whole, it is difficult for the nation to accept large numbers of immigrants. However, it is possible for individual companies to accept foreign executives and workers. Encouraging diversity within an organization could cause internal conflicts and tensions, but if these are effectively redirected outward, they could drive global competitiveness.

Ulrike Schaede The decline in the working population is of course real, and it is a challenge. But it also offers three key opportunities. The first is the opportunity to promote digital transformation. Japan is actually quite fortunate, in that it is experiencing the trends of an aging population, shrinking society and the digital transformation at the exact same time. Many in the U.S. and Europe see digital transformation, robotics, AI etc. as a threat. But for Japan, given the labor shortage some of these automated systems are truly useful at this moment in time.

The second trend is Japan’s outward bound foreign direct investment (FDI). This has been going on since the mid-1980s, and as a result, Japanese companies have built a vast global production network. The automobile and electronics industries have been at this for a long time, but more recently, we are seeing insurance companies, banks, beer companies etc. all extending abroad. That is where the demand is, and also the supply of labor. As a result, given current challenges with de-globalization and tariffs, Japan actually is somewhat protected, compared to other countries.

The third is the domestic change in employment expectations and systems. Foreign workers may be necessary, but what’s more important first is to allow greater job mobility, so that people find the jobs they want to do. This is already happening of course. It is a great threat for companies, who need to worry about how to attract and retain great employees. But it is also an opportunity for companies to rethink the HR function as a strategic function.

Takashi Muraoka FDI and M&A, can be understood as a collective job mobility in some sense. The Japanese perform well as a group, so if management refines the necessary skills to become a collective that excels at M&A, Japanese companies could grow significantly stronger.

Ulrike Schaede Interestingly, it is often said that Japanese companies are not good at M&A, including that they are too slow and not able to accomplish full integration. But to me the impression is that they take a unique approach that differs from the U.S. – and that does not make it better or worse, just different. Studies show that American companies are much quicker at decision-making: they see a deal and they take it. But here is the study I’d like to see: how many M&A deals have failed because they were rushed, or how many unwise deals have American companies made? I would then like to compare that number with how many opportunities Japanese companies lost because they took too long to decide. I don’t know who would come out ahead in this. We can’t do this study because too many M&A deals are private and we don’t know the counterfactual, but I wouldn’t be surprised if this is yet another example of different costs and benefits, not better or worse.

Why Mainoumi Could Create a Diverse Set of Techniques

Takashi Muraoka Professor Schaede, you also draw attention to Japanese companies that hold a very high, or even100% global market share in advanced product categories. In those cases, don’t they fall into excessive competition with other Japanese companies, and eventually become structurally unprofitable?

Ulrike Schaede If a company has a 100% market share, by definition there is no competitor. That’s a very powerful position. What you are alluding to are product categories – for example, in super-advanced, frontier semiconductor materials – where several Japanese companies of mid-size all compete for the best new thing. That is in fact a characteristic of that industry, and one wonders why there is not more consolidation. But the important thing is whether these companies are price-setters or price-takers.

If you look at my chart with the “smile curve”, which graphs profitability for each of the production stages, the entry of first South Korea, then Taiwan, and then China have wiped out the margins in the assembly stage. But the curve indicates that at the upstream stages with difficulty-to-make, difficult-to-copy input materials, profit margins are much higher. If a company can produce such advanced inputs, it should be able to be a price setter. And since this area requires advanced technology, it makes it challenging for other companies to enter.

When I asked the management team of a leading company, “Why are you so profitable?”, some of them simply responded, “We do not do business that does not generate profit”. These leading companies are constantly working on technological innovation, which affords them a position at the forefront of technology with high profitability. I use the image of sumo, and refer to those leading companies as “Mainoumi” athletes. Mainoumi was known as the “department store of techniques”, meaning, innovative strategies that allowed him to defeat his contemporary rivals such as Konishiki, who was much bigger and heavier. What made Mainoumi remarkable was his ability to constantly develop new waza (techniques), so he staid a step ahead of his competitors.

Takashi Muraoka My question here is, why was Mainoumi able to perform a diverse range of techniques? In other words, why are some Japanese companies able to constantly drive innovation? What is the source of power that lies underneath their organizational capabilities? I assume that Mainoumi didn’t focus on practicing new techniques directly, but rather adopted a different training approach from the larger sumo wrestlers. His new techniques likely emerged naturally from his efforts to leverage his agility and speed.

Ulrike Schaede When I met Mainoumi-san, we discussed exactly that. First, he mentioned hard work. This didn’t come to him on a whim; it was the result of deliberate effort. Second, he is an outstanding strategic thinker. He was creative, innovative, and prepared for the competition.

One thing I realized when I interviewed the senior managers of the leading companies was that they had were outstanding leaders who created an organization with a vision. They also had excellent R&D divisions, and HR processes that enabled individuals to innovate. This was possible because they had created a corporate culture that invited experimentation. The extent to which a company allows employees to provide ideas and try new initiatives – this organizational capability is built by leadership, and is a choice that reflects the kind of company they wish to create.

The Strength of Japanese Companies Lies in Their Ability to Manage Complexity

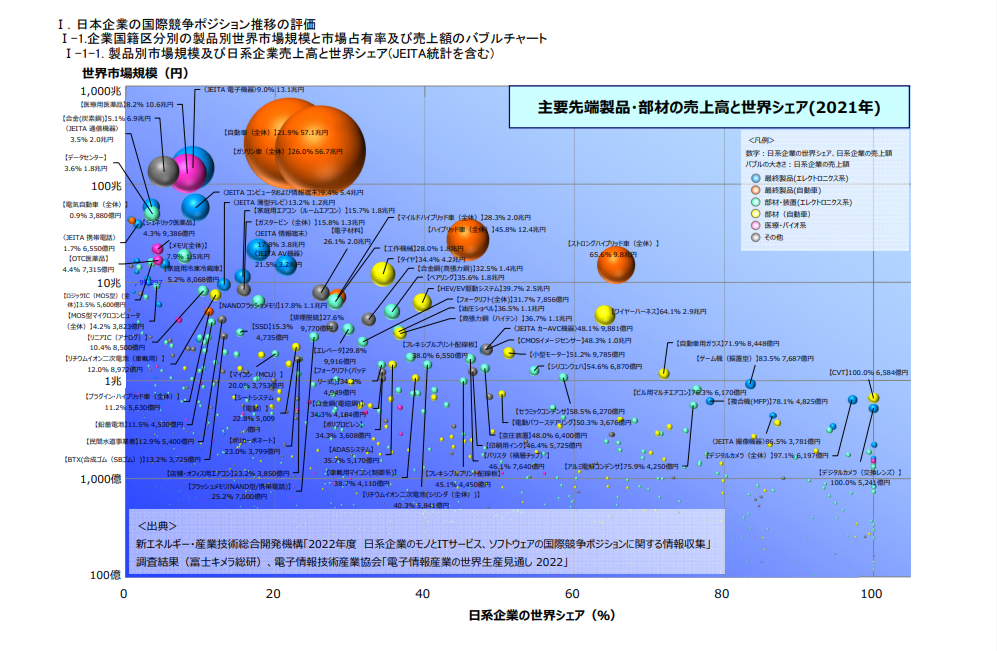

Takashi Muraoka What you just shared made me realize once again that designing a company is essential for building its organizational capabilities. When considering the future of Japanese companies, the graph made by NEDO (New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization) on the total global market share of Japanese companies provides valuable insights. Should Japanese companies expand into untapped markets, or are there alternative options?

Source: 2022 accomplishment report: 2022 Information gathering related to global competition position of Japanese enterprises’ IT services, software, and things.

Ulrike Schaede We should also note that in the above chart, all of these markets are several billion US dollars, so they are not tiny. At a very basic level, global market share reflects dominance – and thereby also pricing power. This power is more relevant strategically than the overall market size itself. A company’s strength lies in its technological leadership. This is true also in small market, or perhaps even more so there, because the development costs for advanced technologies are high, and if the market is somewhat limited, that creates barriers to entry for other from a return-on-investment (ROI) perspective.

It is not a coincidence that a company finds itself in a market where it is difficult to create or copy its products; it is the result of a conscious choice in their positioning. For example, the materials company JSR was originally a synthetic rubber company, but now they are a leader frontier materials for the production of semiconductors, electronic components, and biotechnology. They recognized that rubber had no future, and made a strategic pivot to future chemicals by leveraging their expertise.

Different industries require different strategies and designs. Some industries benefit from economies of scale, and some industries are driven by the power of technology. How to translate the insights derived from Mainoumi differs by industry.

Takashi Muraoka That is true. The strength of Japanese companies will continue to lie in their ability to meticulously manage product complexity including advanced technology. I believe this capability can be traced back to the era of “takumi”, or craftsmanship.

Ulrike Schaede There are two aspects to complexity. The first is the complexity of products, such as photoresists, photomasks, and mirrors used in semiconductor manufacturing. Beyond the complexity of the product itself, Japan also excels in managing complexity in processes. For example, no other country in the world can match Japan’s precision in operating trains on schedule. Some people may downplay the value of craftsmanship and manufacturing, but even Google and AWS (Amazon Web Services) rely on hardware. The ability to optimize is crucial, and presents a significant opportunity.

Takashi Muraoka Applying the strengths to new external environments, technologies, and geopolitical changes is also another important factor of complexity. Japanese companies are in the midst of incorporating new complexity management skills, including those for new technologies like generative AI. By overcoming this stage, Japan is sure to reach new heights. Of course, this next stage will have its own competitive landscape, so companies must strategically define their focus area, just as Mainoumi strategically chose his own battles. The role of leadership will be even more critical, as they must set a strategic direction for the future. However, this should not be viewed negatively.

Ulrike Schaede I agree with the complexity and system optimization. Even though Japanese companies can do a lot in the current DX, pessimism persists within Japan. I believe one reason is because the New Japan strength is difficult to see. If there were a “Japan Inside” sticker, like the “Intel Inside” sticker on Windows computers, it would pop up everywhere in daily life. However, in reality, the contributions of Japanese companies are extremely hard to see. On top of that, their complexity makes it even more difficult to come across opportunities to recognize them. Despite this, the market shares speak for themselves. By learning more about such information, people will eventually realize that there’s no need to be so pessimistic about Japan’s situation.

An Era Where Qualitative Growth is Key

Takashi Muraoka Lastly, please give a message to Japanese companies.

Ulrike Schaede The main message I would like to convey is the definition of “growth” going forward. In the past, “growth” referred to the revenue and headcount of large companies, or a country’s GDP. However, moving forward, I believe quality will be what matters most. By qualitative growth, I mean the growth of technological leadership, knowledge, and sustainability – in other words, growth towards becoming a better country and company.

This is where Mainoumi’s strategy serves as a model for Japanese companies. Not Konishiki, who won against other sumo wrestlers due to his large physique, but Mainoumi, who cleverly and intelligently integrated all of his techniques. In today’s age of global competition, size can offer an advantage, but it will not determine success. Leaders are now expected to drive qualitative growth, make the company more agile, and hold a compelling vision and purpose for the future direction.

IGPI Group encourages the qualitative growth of various players, such as large companies, startups, universities and local companies, through its consulting and investment activities. Your activities have generated numerous new opportunities that are difficult to replicate, and I look forward to seeing them continue.

Takashi Muraoka As environmental changes accelerate and become more complex, responding with agility requires not only speed but also quick initiation. If you swiftly prepare and act, even if your pace is slightly slow, you will reach your destination quicker. As IGPI Group, we hope to serve as leaders, helping Japanese companies develop the responsiveness to adapt to such changes.