When History Moved with the IGPI Group

Under the purpose statement of “Pioneering a new era of management”, IGPI Group has been challenging Japan and the world on the “ideal form of management” in various types of organizations. Since the time of the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan (IRCJ), where many of the founding members of IGPI were involved, through the Great East Japan Earthquake and Abenomics up until the present day, how has IGPI Group worked with the Japanese and global management and economy? We hear from Keita Nishiyama, IGPI’s Senior Executive Fellow, and Kazuhiko Toyama, Chairman of IGPI Group, speak of the path taken by IGPI and the Japanese economy while also sharing their thoughts at the time.

The limitations of the Showa model and the emergence of the IRCJ

Keita Nishiyama I first met you, Toyama-san, in 2002 when I had been seconded from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) to the Cabinet Office and was working in the IRCJ’s preparation office. A few years prior, there was a time I had traveled to Europe and the U.S. to investigate insolvency laws overseas. Back then, Japan still did not have its Civil Rehabilitation Law, and there were discussions on the need for such legislation. As a result, I spoke with various experts in the field of restructuring in the western countries, including judges, lawyers, and expert witnesses. For example, in France, I visited special courts that handle only corporate legal matters, separate from the general judiciary, and based on the idea of “merchant autonomy”, the judges are not lawyers but actually businessmen who serve for a fixed term. What I realized then was that even if you set up laws and systems, they will not function unless you have the people who could support the ecosystem that operates them. This is why I believed it was important for the IRCJ to involve professionals like Toyama-san, to build the mechanisms and people that could support the software and ecosystem necessary for corporate and industry restructuring, as well as disposal of non-performing loans.

Kazuhiko Toyama When I was studying law long ago, I read a book that stated, “The degree of evolution and maturity of bankruptcy legislation is equal to the degree of maturity of the country’s capitalism”. As I got involved in corporate restructuring, I felt that Japan’s success model was premodern, its legislative system underdeveloped and capitalism still premature. Even if Japan reached the stage where it must drive its growth with innovation and corporate metabolism, it would be unable to transform its industrial structure. When the country was considering its policy to prepare 10 trillion yen to dispose of non-performing loans, there were a few people including you, Nishiyama-san, who shared the same perspective as me. This is how the IRCJ came to be – with these like-minded individuals, we were determined to get to the root cause of Japan’s economic system, which was maladapted to the times in terms of structure, human resources, and ecosystem.

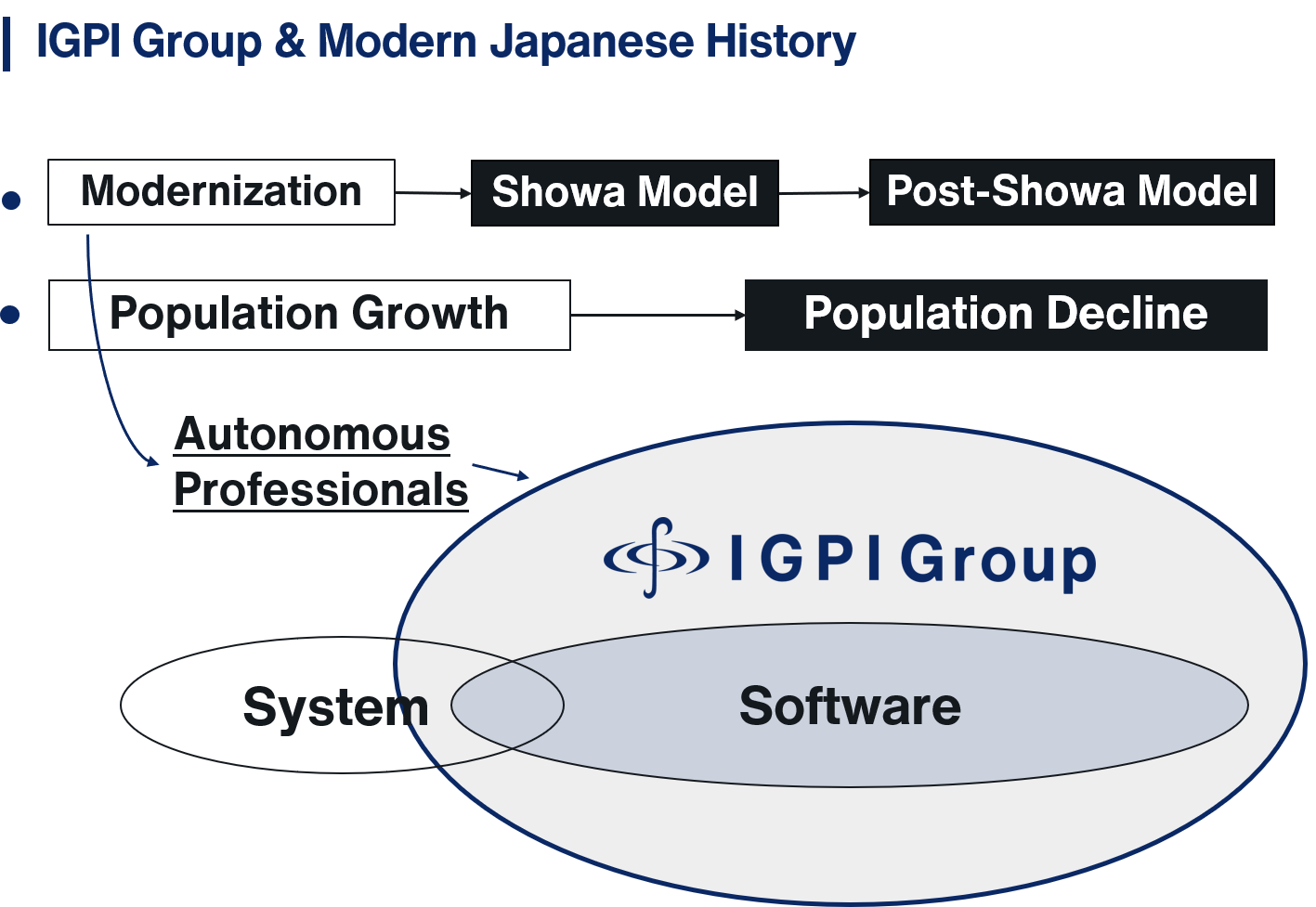

Keita Nishiyama The bankruptcy law and insolvency proceedings were the first clear example of how the Showa model software was incompatible with the current era. Japan had rapidly modernized with the government’s lead; however, even if systems could be replicated, when it came to software and ecosystem, there was only so much the government’s initiatives could do, and it would take more time. I believe cultivating autonomous professionals has been a long-standing issue for Japan ever since the Meiji era. As we now face the challenge of population decline, there is a need to create the “Post-Showa model”, and to nurture professionals and ecosystems that could support that new model. These, I believe, are the common themes that underlie the activities of IGPI Group.

Kazuhiko Toyama You’re right. IGPI’s history begins from the IRCJ days. In the 1990s, Japan suffered from the problem of non-performing loans, and many banks collapsed with the financial crisis. One reason for this situation was that back then, all legislative systems and values people held were based on the notion that companies could not go bankrupt. Economists simply said that if you could not pay back the money you borrowed, you could exit through insolvency proceedings. However, none of the stakeholders in question had the incentive to do that. Once you enter insolvency proceedings, the management would be dismissed, or worst case, sued. Employees would be laid off, and banks would be pressured to waive their debt. For shareholders, their stock certificates would lose their value. These were the reasons why insolvency proceedings had been postponed.

In addition, banks themselves were also in a crisis, and thus their disposal of non-performing loans could have triggered a chain reaction of insolvencies. In the Showa model, banks also assumed the role of equity holders, and gave loans secured by real estate. If they valued their drastically diminished real estate at market value, the banks would suffer from a further increase in non-performing loans, which they did not want. Therefore, they turned a blind eye and did their best with very high book value, despite being aware that it was all a fictitious narrative. Basically, discussions were stuck in many aspects during this time. How was this situation from a government official’s perspective?

Disposing of non-performing loans is equal to liberating humans

Keita Nishiyama One cause of Japan’s financial crisis goes back to the 1980s, a period when Japan was done with its rapid economic growth and should have been thinking of its next steps. Unfortunately, Japan got carried away with being called “Number One”, and decided to invest its wealth into the old model when it should have been focusing on something else – developing a new organizational principle that differed from the existing model of having a main bank and companies providing lifetime employment. However, when the economic bubble burst, Japan thought that if we endured this time now, we would eventually return to the old model; thus, change did not occur. Since there is strong peer pressure in Japanese society, we need someone to stand out as outliers to bring about change in the organizational principles. There is a need for “autonomous individuals” who are not entirely assimilated in the organization to start thinking of new systems.

This is why, as a principle, we involved independent professionals to manage the ICRJ. If we involved individuals who represented certain companies such as banks, we would have not been able to operate fairly. We also implemented a timeline for the ICRJ. The system for the disposal of non-performing loans had been established in the 1990s, but it did not solve anything except for simply transferring loans to public organizations to be held indefinitely. We wanted to have a fixed deadline of a few years and produce clear results within that time frame.

Kazuhiko Toyama I also held similar principles. This is why I made sure the ICRJ became a professional-led organization, and did not accept individuals who came with strings attached. As a result, we first saw the battle between Showa and Post-Showa values emerge. Then came the second battle over the (corporate) valuation of the acquisition of debts. While we used the DCF (Discounted Cash Flow) method, the banks used book value. Some individuals even expected us to take the approach of covertly injecting public funds to transfer the non-performing loans. Though that may have been the quickest to process, it would not have fundamentally resolved the issues. This was also where we had conflicting opinions.

We mustn’t forget that these individuals who wished to protect the old system were not amateurs; they also held ample knowledge and expertise in the field. This is why we assembled top-notch professionals who could easily make a living in the private sector to do this work, so that they could compete with each other equally. We presented this as an absolute condition from our end, but thankfully, Mr. Sadakazu Tanigaki, the minister in charge, agreed to it as well. Out of all the public-private funds at the time, the ICRJ was the only one that executed according to these principles.

Another point was that if the ICRJ simply acquired the debt, that would only be a temporary solution, as it would soon become non-performing loans again. This is why I believed it was essential to make an equity injection and get involved with the management, just like a PE Fund. However, there was surprisingly quite a bit of resistance with this as well, because this would imply a form of nationalization. Some people still believed that the falling of real estate prices and collateral values was momentary, and that they would return to normal if they waited long enough.

Keita Nishiyama I also agree that if we resort to temporary solutions during a corporate turnaround, we would be wasting our valuable human resources. Disposing of non-performing loans is essentially the liberation of humans. Back then, both the banks lending money as well as individuals borrowing money were busy preparing large volumes of documents in an attempt to make excuses. We must liberate people from such work, and engage them in more empowering, forward-looking jobs, or else there would be no future left for the Japanese economy.

The establishment of IGPI: cultivating management personnel and transforming companies in the long run

Keita Nishiyama What were your aspirations when you founded IGPI?

Kazuhiko Toyama Fortunately, the non-performing loan problem was resolved by 2005. Insolvency proceedings became regularly executed, PE funds were growing, and we had achieved the mission in terms of policy objectives. When I thought about our next steps, there were a few remaining themes.

Firstly, one common issue in corporate restructuring, regardless of the size or industry, was the lack of management personnel. There were many individuals who worked great as employed, “salaried” managers in an environment where there is an increasing population and steady economic growth, a playbook, and while Japan was still in pursuit of catching up to the western countries. However, we needed to accumulate proper management personnel that held their own will and values, and could pave their way across the turbulent social structure in Japan.

The second challenge that remained was our limitation with time. With the two years that were given to ICRJ, it was possible to achieve a V-shaped recovery as long as we cut down unnecessary excess. The problem was what came after, where we saw the battle to transform the company to adapt to the new era. I believed we had to somehow obtain long-term funding to make new investments and hire new people.

The founding members of IGPI had been receiving numerous offers with high compensation from companies, but we asked ourselves, would we be satisfied with choosing such a typical, conventional career path? Since everyone shared this mutual feeling, that was why we all came together to found an organization in the private sector that solves the remaining challenges. In doing so, I did not want this company to become a “Toyama & Co.”, but rather a professional organization run by partnerships, similar to an accounting or law firm. I wanted this company to grow into a Japan-born organization that lasts for another 50 to 100 years. This had to be, as my life is finite, and we would be in trouble when the time came for business succession. I was sure that IGPI would be successful since we had few competitors. It was clear that IGPI’s enterprise value would rise, and then it would be difficult to transfer shares. If we tried to go public from there, the company’s growth trajectory and narrative would fall out of place. This is why I founded IGPI as a partnership model company with everyone entitled to equal shares.

Keita Nishiyama While the Showa model focused on company names and titles, eccentric individuals that aim for professionalism without caring too much about social hierarchies can show their full potential when they all come together. I believe that IGPI has made this kind of organization possible, where such individuals can gather and collaborate.

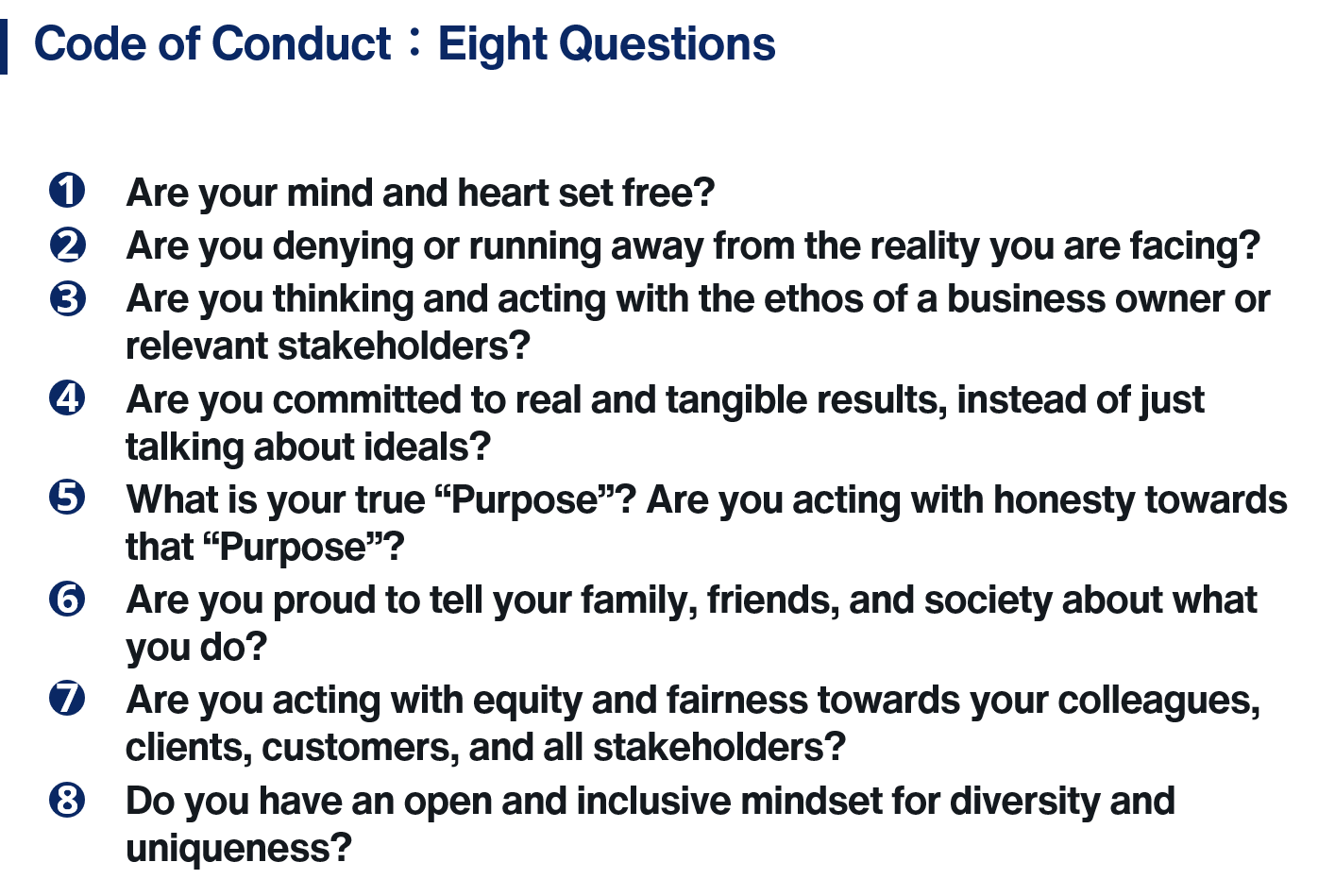

Kazuhiko Toyama Of the Eight Questions in IGPI’s Code of Conduct, I believe the question, “Are your mind and heart set free?” is extremely important to a professional organization. The Japanese kanji characters for the word “free” (自由) translates into “originating from the self”. Basically, you have your own worldview and values, and that becomes the basis of the thought process behind your actions and decisions. On the other hand, acting based on an organization’s norms is the opposite, “originating from others” (他由).

However, in order to remain free but united as a group, there must be some form of shared values. If the objective is to simply pursue short-term growth as a business, it is better to work towards one economic goal with centripetal force, in which case diversity becomes a hindrance. In other words, it’s a crucial decision to prioritize diversity over short-term growth. I made sure that the organization would serve as a kind of Liangshan Marsh – a place of assemblage for the bold and ambitious – where it could function effectively even if it attracted the oddest people.

The end of the Showa model and towards a two wheeled model of L and G

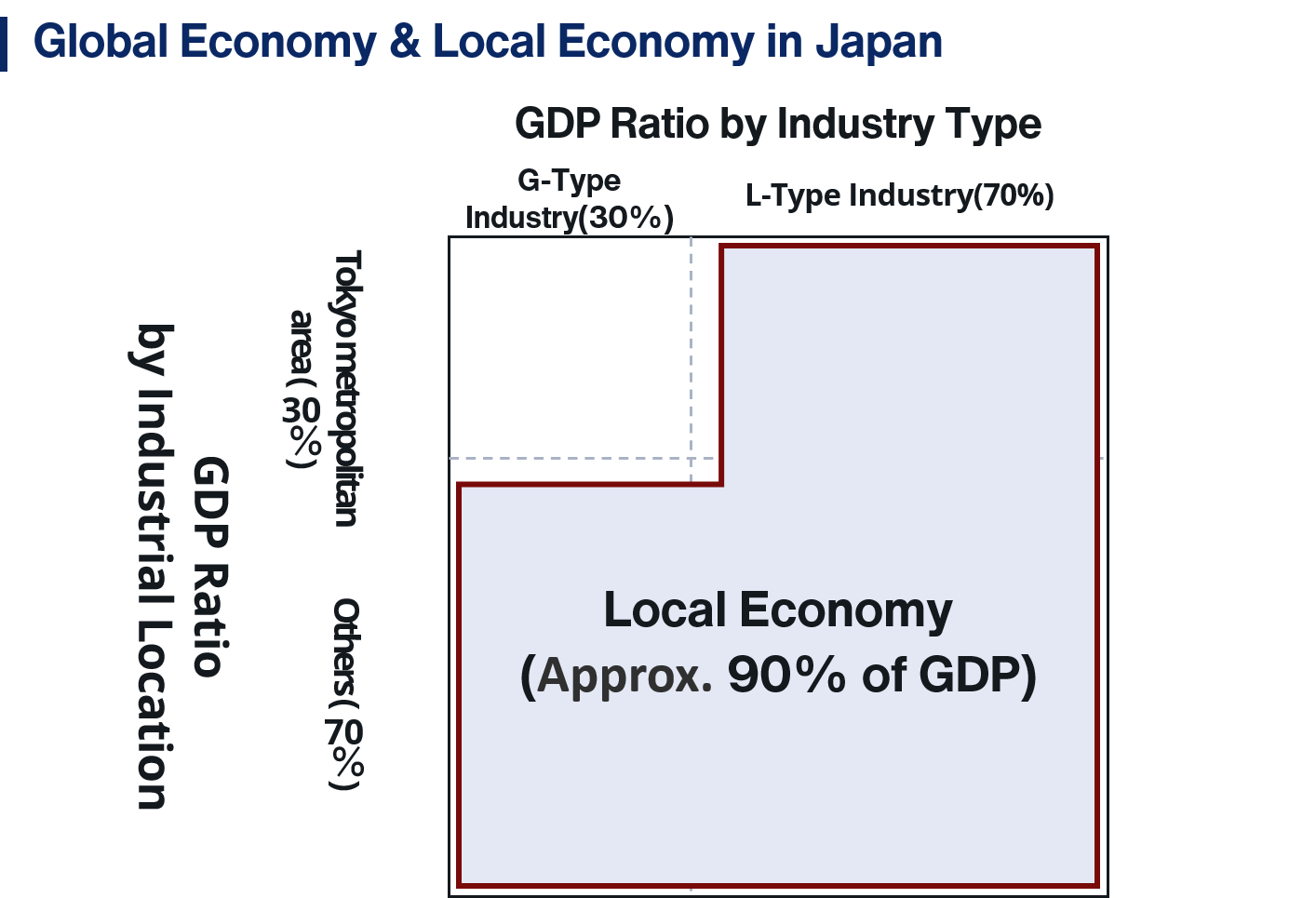

Kazuhiko Toyama At IGPI, we had the opportunity to rebuild a bus business in the Tohoku region. What we realized there was that the local economies function on a different set of principles than global industries. At the ICRJ, the companies we restructured always faced the issue of excessive personnel, but in Tohoku, there had been a shortage of drivers since over a decade ago. This was because young people had left Tohoku for Tokyo, and the overall population was in natural decline. It was true that the economy was in steady decline. However, because the supply of labor had been declining from before, this reality differed from the commonly held belief that people were leaving because there were no jobs in the rural areas. When I discussed this with you, we talked about the difference between G (Global) and L (Local) – it was a very unique perspective that you presented.

Keita Nishiyama Around 2008, when we discussed the topic of regional healthcare, I realized there was no policy based on industrial organization theory. Regional healthcare should be a combination of emergency hospitals followed by residential hospitals and primary care physicians, but measures were only considered for each individual clinic. Furthermore, METI was trying to refer to all industries in terms of manufacturing technology, but this does not apply to most small and medium-sized enterprises. As I looked for something in common, it came down to the topic of G and L.

Kazuhiko Toyama After abstracting and universalizing the concept, we realized there is much value for IGPI to seriously work on the local economies. It is often believed that the G economy is larger in Japan, but in reality, it is the L. I had even originally thought the former, so it was a turning point for me. It led me to write the book that eventually became one of the triggers for the beginning of regional revitalization policies throughout Japan.

The Michinori Group had a rough time since the Great East Japan Earthquake, but they managed to overcome the struggles as they handled evacuation transports from the nuclear power plant accident. After the nuclear accident at TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power Company), we worked together with TEPCO to build the basic scheme for nuclear damage compensation, but looking back in history, I believe that signified the end of the Showa model.

Keita Nishiyama The nuclear division at TEPCO was similar to the semiconductor sector at general electric companies. They believed they held the most leading technology in the company, and assumed they were the only ones who understood. This leads to a lack of will to learn from other fields, therefore halting evolution even in the field of safety.

Kazuhiko Toyama Then they could never innovate, nor could they welcome new innovations.

Pouring our heart and soul into the corporate governance reform

Kazuhiko Toyama In the subsequent phase of Abenomics, the main issue was how the industry as a whole could move away from the Showa model. I was confident that not only finance was stuck in the old model, but all industries were suffering from the same mindset. The most successful institutional reform under Abenomics was corporate governance reform, but in order to transition models, we had to start changing from the top, as if it were from the bottom-up then nothing would fundamentally change. This was also the time when IGPI decided to actively engage in this transition, and allowed our partners to take on positions as independent directors.

Keita Nishiyama In 2013, I borrowed the title of your book and founded the “Earning Power Study Group” at METI. The Corporate Governance Code is very effective in using earning power as a KPI to restructure a company’s system. At the same time, even with the Code, the management must be able to first think for themselves. This is contrary to the usual notion of “comply or explain”; rather, it is the notion of “explain or comply”. First, one must rationally choose their own preferred management structure, and explain to external stakeholders in their own words. If they cannot think of any ideas, they may borrow from the Code. This is related to the idea of managing business as one independent individual, as opposed to simply taking on the role just because it is now their turn to do so.

Kazuhiko Toyama The reason why I started using the term “earning power” was because I was contemplating why Japan was no longer able to earn. This was because the Showa model of massive investment into facilities, mass production, and global mass sales had transformed into mass employment of new graduates and lifetime seniority system – an institutional theory as called by Professor Masahiko Aoki – and this was no longer applicable in today’s world. To get rid of this model, we needed more diversity and dynamism in the organization, but such an approach was not suited to Japanese companies. We needed a more fundamental reformation, or “corporate transformation (CX)” as IGPI calls it; without it, we were left in a dire situation. For this approach, we had to start with the appointment of management. Everyone was eyeing who would become the head of the organization, so if we changed this, then the whole organization would also change at once. This was why I was fixated on delivering corporate governance reform.

Initiatives for the AI revolution

Kazuhiko Toyama After eroding the Showa model came the challenge of IT. It was around that time when I met Professor Yutaka Matsuo from the University of Tokyo, and felt a historic industrial revolution coming with AI. As with the industrial revolution replacing muscle work, and the IT revolution replacing perception, I felt that the AI revolution would replace the brain. This was when I decided to work on something much larger scale, and called up Nishiyama-san to join me in making history.

Keita Nishiyama With your introduction, I invited Professor Matsuo to join the Earning Power Study Group. We needed to nurture more data scientists in order to lead Japan with AI, so with that purpose, The University of Tokyo Global Consumer Intelligence (GCI) was established. Currently, the program provides data science courses to over 10,000 students each year, including students from outside the University of Tokyo. The reason why this program became so popular is because it is structured in a way that students can teach the younger students. Teaching is the most effective way to learn, and it prompts them to think on their own. This helped encourage alumni to start their own business. In this way, we are starting to see an ecosystem around AI and startups being built.

Kazuhiko Toyama When a revolution occurs, that is when new startups arise. It is inevitable that a lot of startups emerge around Professor Matsuo. That is why I wanted to delve deep into this field.

At IGPI, we partnered with the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and started a venture capital firm in the Nordic and Baltic region called Nordic Ninja. We had been involved in building the startup ecosystem from the late 1990s, such as with the University of Tokyo’s Technology Licensing Organization (TLO) and The University of Tokyo Edge Capital (UTEC), but I was always concerned that there were not enough global ties. If we were to create a hub, rather than creating it in the Silicon Valley where it is already a red ocean, I thought it would be much more interesting to focus on the Nordic region where a new global system is already being formed.

What all of these new initiatives have in common is that, while I may be the one who initiates, there are always other partners that are willing to seriously get involved. I believe that this was possible because we are a Liangshan Marsh that attracts individuals that wish to actively engage in projects at their own will.

continued in the second half